PROFESSOR Martijn Katan is a biochemist and emeritus professor of nutritional science. For thirty years, he tried to prove that raising good cholesterol levels in your blood protects against heart attacks, but in the end, he has concluded it simply doesn’t.

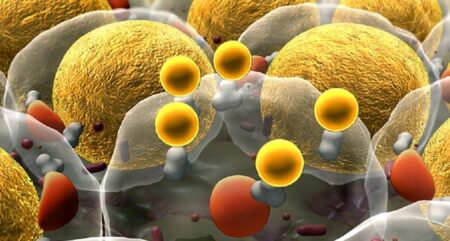

Cholesterol is a fat and is always bad if it stays in your blood. Cholesterol is transported through your arteries in tiny balls wrapped in a thin layer of protein. If it stays within this layer, no damage is done.

Good cholesterol is wrapped in a high-density layer of protein. This lowers the chance that the cholesterol escapes into the bloodstream, where over time it can block arteries, which can lead to a heart attack.

Bad cholesterol is transported in a low-density layer of protein. This means there is a much higher chance it will escape into the bloodstream and cause harm.

A quarter of cholesterol in the blood tends to be wrapped in a high-density layer, the rest in a low-density layer.

For a long time, nutritional scientists tried to prove the hypothesis that high-density wrapping sucked up cholesterol which had escaped from low-density wrapping. If this were true, so the theory went, heart attacks could be prevented by raising a person’s high-density-wrapped cholesterol levels.

One way of raising high-density-wrapped cholesterol is to drink alcohol, hence the medical advice, which proved to be immensely popular, to drink two glasses of wine a day. Professor Katan notes that this advice is now obsolete, and that drinking alcohol in any form and quantity is bad for you.

Professor Katan’s research extended to other food stuffs. It found that carbohydrates (bread, pasta and sugar) lowered levels of high-density-wrapped cholesterol. If the hypothesis about good cholesterol sucking up bad cholesterol and preventing heart disease in this way was true, you should obviously stay away from carbohydrates.

Eggs, Professor Katan found, increased both levels of low-density and high-density-wrapped cholesterol, so they cancelled each other out: eggs therefore didn’t do much harm. If … the hypothesis was true!

But Professor Katan began to question whether there was enough evidence to justify nutritional advice to increase artificially the levels of high-density-wrapped, good cholesterol in blood.

While it was certain that low-density-wrapped, bad cholesterol caused heart attacks, there wasn’t really anything to suggest that good cholesterol absorbed bad cholesterol, thus reducing the risk of heart attacks.

For example, among people who for hereditary reasons had no high-density-wrapped cholesterol in their blood, there was proportionally the same number of heart attacks as among people with normal levels of high-density-wrapped cholesterol.

Then medicines which increased levels of high-density-wrapped cholesterol were developed and tested on thousands of people. That’s when it turned out that no reduction in the number of heart attacks resulted from taking these medications. There was also no reduction in the clogging of arteries.

This meant that low levels of high-density-wrapped cholesterol did not cause heart trouble. It only meant that people with low levels of high-density-wrapped cholesterol were more likely to have heart trouble. The low levels are no more than a signal.

Professor Katan compares a low level of high-density-wrapped cholesterol to the little red light on the dashboard of car which comes on when the oil in the car’s engine needs a top-up. It’s a signal, no more. Just switching off the light will not fix the engine’s need for an oil top-up.

So, the hypothesis on which so many nutritional scientists spent so much time for so long, that high-density-wrapped cholesterol is good and that levels of it in the blood should be increased because it reduces the risk of a heart attack, has been disproved.

This does not mean that you can let rip with any food that takes your fancy. Cholesterol, if released from its wrapping, high- or low-density, is always bad for you.

Therefore it’s wise to avoid as much as possible food that increases levels of low-density-wrapped cholesterol in your blood, because the risk of cholesterol escaping into your bloodstream with this type of food is high.

Bad cholesterol will always be bad, no matter what.

Good cholesterol will always just be not bad.

Unfortunately, that’s as good as it gets.

(This article is a summary of a column by Prof Martijn Katan in the NRC Handelsblad.)